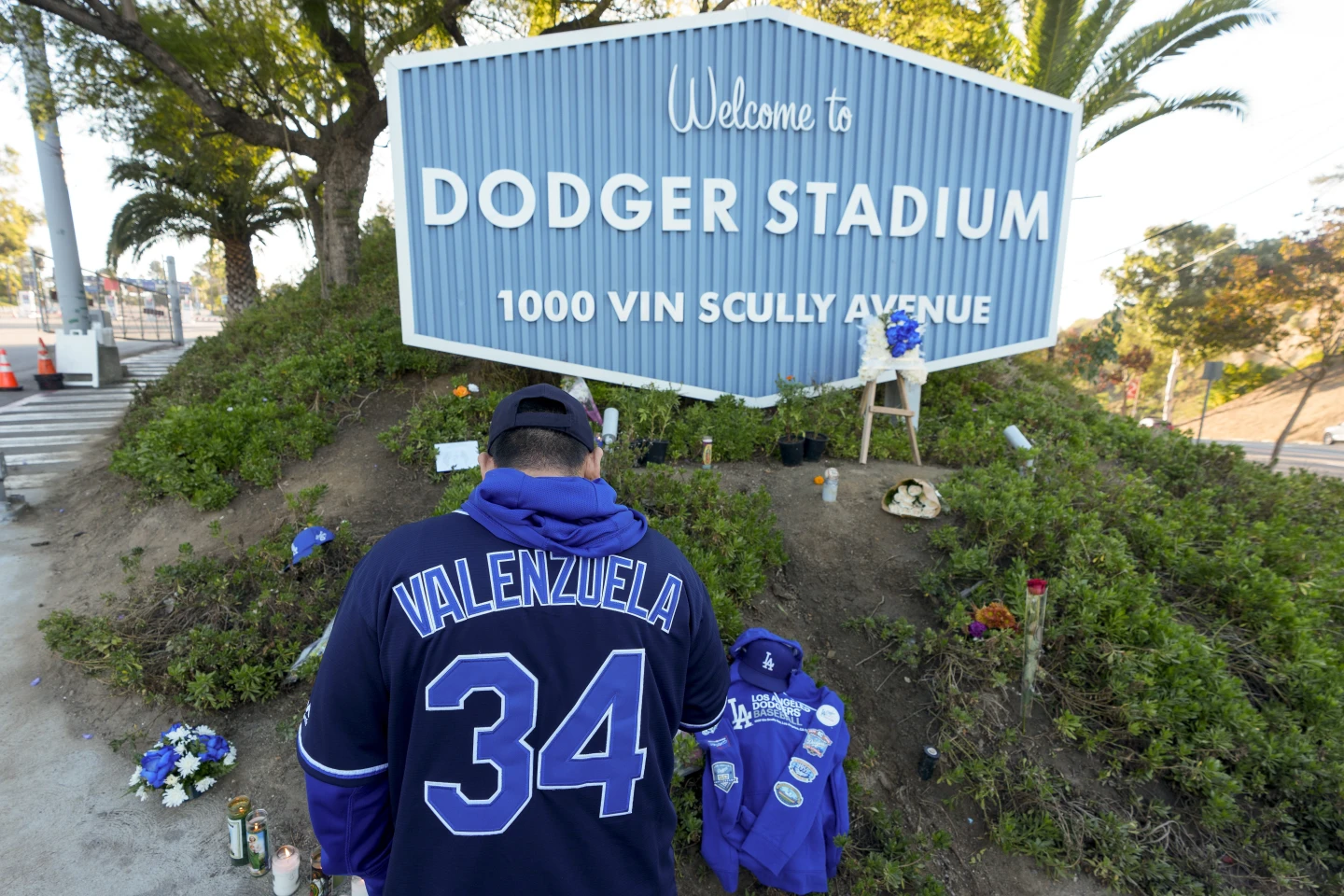

Julia Mendez carefully placed three candles in a row under a sign welcoming fans to Dodger Stadium. Then she took out a burrito wrapped in foil and leaned it against the post.

“I know he ate a burrito all his life,” said the 70-year-old fan from North Hollywood, who had filled the flour tortilla with nopales and scrambled eggs in her kitchen.

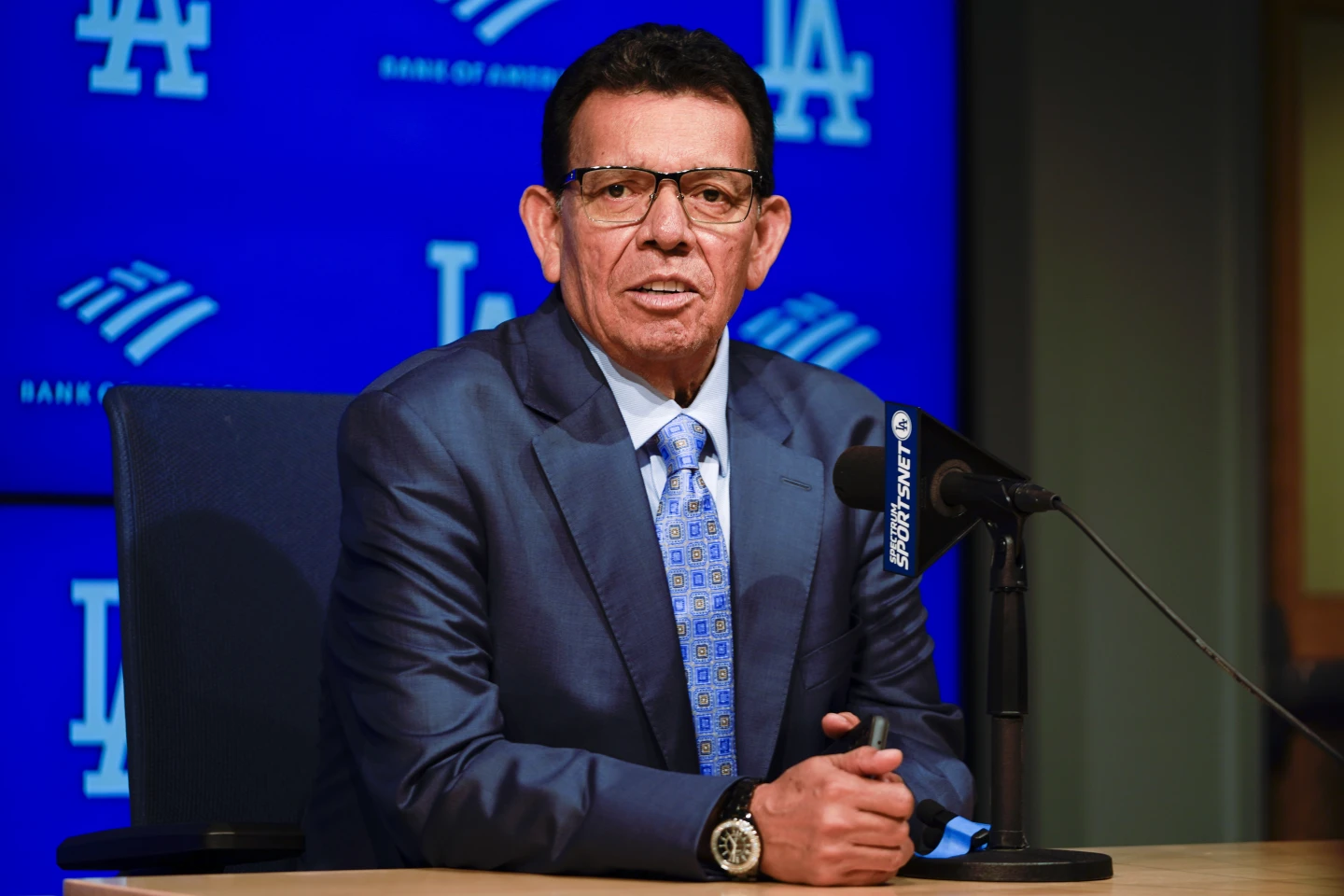

The city of Los Angeles was grieving on Wednesday for Fernando Valenzuela, the Mexican-born Dodgers pitcher who sparked “Fernandomania” with his unique pitching style and impressive performances in the early 1980s.

He passed away on Tuesday night at the age of 63.

“I came here to the United States in 1976. He came in 1979. That’s when all my pride and joy began,” said Mendez, who is from the same Mexican state of Sonora as Valenzuela. “He put our names so high around the world; the whole community became fans. My love for so many years.”

Valenzuela’s journey from being the youngest of 12 children in Mexico to becoming a star pitcher made him very popular and influential in Los Angeles’ Latino community, while also bringing new fans to Major League Baseball. People continued to admire him even after he retired.

Across the street, the mariachi group Garibaldi de Jaime Cuéllar played their guitars and trumpets.

They often perform at Dodger games and were there for a scheduled television interview before the World Series against the New York Yankees. They stayed to honor the man known as “El Toro” with their music.

Major League Baseball and the Dodgers were making plans to honor Valenzuela before Game 1 of the World Series on Friday.

In the left corner of the blue-and-white sign, there was a large sombrero and a colorful serape. Mendez had added white butterfly wings above the second ‘D’ in Dodger. The sign also served as a place for people to gather emotionally in 2022 when Dodgers Hall of Fame broadcaster Vin Scully passed away at 94.

Henry Gomez from Gardena brought his 6-year-old daughter, Tianna, to the growing memorial outside the closed stadium. She was holding a souvenir street sign that they had written on and planned to leave there.

“He’s one of the Hispanic idols for us,” the elder Gomez said. “He opened a lot of doors for a lot of people behind him. We’re proud from that.”

In the Boyle Heights neighborhood, not far from the stadium, Robert Vargas was painting a mural of Valenzuela on the side of a building. The artist, who is of Mexican descent, is known for his large artworks in outdoor locations around the world. His mural of Dodgers superstar Shohei Ohtani on a Little Tokyo hotel has become a popular spot for tourists.

Back at the stadium, three men stood in the shade sharing stories about Valenzuela’s achievements on the mound. Gomez had the opportunity to shake hands with Valenzuela a few times over the years.

“He was really cool, a good guy,” he said. “When you’re famous, that’s the way to be, like Fernando’s way.” Fans started gathering outside the stadium as soon as the sad news came out late Tuesday.

Marcello Ambriz shared a photo of himself as a 2-year-old with the pitcher. “Mexicans wouldn’t be Dodger fans without Fernando,” he said.

The land where Dodger Stadium is located was bought from Spanish-speaking homeowners in the early 1950s by the city of Los Angeles.

At first, the homeowners refused to sell, so the city used eminent domain to take the property from the close-knit Mexican-American families, many of whom had lived there after facing discrimination in other parts of the city.

“There’s a lot of very sad sentiments about that,” Ambriz said. “Fernando was able to somehow mend that. Obviously today there are many people who are hurt and can’t let that go, and that’s understandable, but Fernando’s presence and him being from Mexico was able to unite that.”

Valenzuela would have turned 64 on Nov. 1, when the Dodgers might host Game 6 of the World Series. Next Friday is also Dia de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, in Mexican culture, a time to honor deceased loved ones.

“There’s no reason to be sad because he lives forever in our hearts,” Mendez said. “He accomplished the American dream, more than the American dream really.”